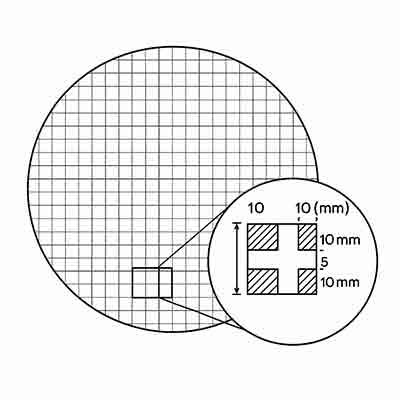

I am a PhD student and currently working on the OPV devices project. Recently, we were trying to make our device on the flexible substrate and would like to try on PEN. Instead of entire Indium Tim Oxide (ITO) on the substrate, I would like to request the quotation of the customized patterned ITO on PEN (sheet resistance from few ohms/sq to 30 ohms/sq) for 25-30 pieces? (pattern below.)

ITO Wafers Used To Fabricare Organic Photovoltaic Solar Cells

A PhD candidate requested a quote for the following research.

Reference #325282 for specs and pricing

Get Your Dicing Quote FAST! Or, Buy Online and Start Your Research Today!

How Efficient are Organic Solar Cells Efficiency?

Here’s a summary of how efficient organic solar cells (also called organic photovoltaics, OPVs or OSCs) currently are — along with some of the key caveats and what they mean for your work in thin-films and MEMS.

✅ Efficiency levels

-

Recent review papers describe lab-scale organic solar cells achieving power conversion efficiencies (PCEs) in the ~15-20% range. For example: one states “the efficiency of organic solar cells (OSCs) recently reached 20 %”. ScienceDirect+2RSC Publishing+2

-

A 2020 paper reports a device with ~17% PCE. OUP Academic

-

Other more general reviews still describe organic PVs as “typically around 5-10%” for many devices, especially older or more standard-structures. PubMed Central+1

-

One more recent publication (2025) mentions that even though efficiency has improved, OSCs “still face challenges, such as lower efficiency and shorter lifetimes compared to traditional inorganic cells.” AIP Publishing+1

⚠️ Important context & caveats

Since you’re working in the domain of wafers, thin films and MEMS/integration, these are relevant:

-

Lab device vs commercial module: The high efficiencies (~15-20%) are largely lab devices under ideal conditions: small area, optimal contacts, precise morphology, etc. Scaling to large area, flexible substrates, printing, real-world conditions often reduces the PCE.

-

Stability and lifetime: Many organic solar cells still have shorter lifetimes (degradation from light, oxygen, moisture) compared to mature silicon or other inorganic PVs. Efficiency might degrade substantially over time. The “effective” efficiency over many years may be much lower in practice.

-

Fill factor, Voc, Jsc limitations: Many of the losses in OSCs come from non-radiative recombination, lower open-circuit voltages, lower fill factors compared to inorganic PVs. For example, one work identifies that even high-efficiency OSCs have significant charge‐transport resistance limiting fill factor. arXiv+1

-

Material and layer thickness trade-offs: Because organic semiconductors often have shorter exciton diffusion lengths, the active layer thickness is constrained, morphological control becomes very critical, and achieving high current densities (Jsc) and high Voc concurrently is more challenging.

-

Application niche: While the efficiency is still lower than best inorganic cells (e.g., silicon, perovskite), organic PVs bring advantages like flexibility, low weight, potential for roll-to-roll, new form-factors (curved surfaces, wearable, transparent). So the “effective” performance metric might include weight, flexibility, integration rather than just PCE alone.

🎯 What it means for your work

Since you’re working in thin-films, MEMS and substrate integration (including wafer-based and optical MEMS device contexts), here are some implications:

-

If you consider integrating organic PVs on wafers or as part of sensing/optical alignment systems, expect PCEs in the realistic range of perhaps 10-15% (or less) for full‐scale usable devices rather than the >15% lab champion numbers.

-

Because you deal with wafer and substrate issues (bowing, cooling, thin film coatings), the integration environment (substrate, thermal expansion, mechanical stress, encapsulation) will further influence performance and lifetime of an organic solar cell.

-

If you use OPV devices as part of a sensor or power source (rather than large scale utility grid feed‐in), you might be more concerned with area, weight, flexibility and mechanical integration rather than just maximizing PCE.

-

If substrate cost / mechanical integration cost dominates, the lower cost manufacturing and flexibility advantage of organic PV might outweigh somewhat lower PCE for certain niche uses (e.g., conformal sensors, low‐power integrated MEMS).

-

But if you compare to inorganic PV or silicon‐based module alternatives (which might have 20%+ PCE and decades of lifetime), you need to factor in the trade-off: lower PCE + shorter lifetime vs more flexible form‐factor and potentially lower cost/weight.

What isThe Price for Organic Solar Cells?

The price for organic solar cells (also called organic photovoltaics or OPVs) is still quite variable because the technology is emerging and not yet mature for large-scale deployment. Here are some indicative numbers and caveats:

✅ What we know

-

One review estimates that manufacturing cost for purely organic solar cells could range US $50-140 per m², assuming about 5% efficiency. ScienceDirect

-

A recent development reported that a new polymer material for organic solar cells could enable a minimum sustainable cost of ~US $0.36 per watt (US$/W). Notebookcheck+1

-

A UK-based article estimates that end-product panel cost (when/if produced at scale) might be between £40 and £150 per m² (~US$50-190/m²) for organic PV modules. The Eco Experts

-

On the wholesale component trading side, listings for “organic solar cells” show extremely low per-unit prices (~US $0.07–0.09) but these are likely very small pieces, non-standard, and not reflective of full module performance or lifetime. Alibaba

⚠️ Important caveats

-

The efficiencies of organic solar cells are still generally lower than mature silicon or other inorganic PV technologies; while some recent work is approaching ~20% for lab devices, commercial stability is still a concern. The Eco Experts

-

The lifetime (durability, degradation) of organic solar cells has historically been much shorter than silicon modules, which affects cost-effectiveness. The Eco Experts

-

The “cost per watt” figure (~US$0.36/W) is a minimum sustainable cost projected under certain lab conditions/materials; scaling to full modules, packaging, field use, installation will add further costs. Notebookcheck+1

-

Because large-scale commercial production is still limited, many price quotations are for small-batch or experimental modules, which may not yet reflect mass-production economies.

🔍 What that means for you

Since you’re working in MEMS / wafer / thin-film research, if you’re assessing organic solar cells for substrate or device integration, you might think in terms of:

-

Material cost: e.g., polymer cost of ~US$35,000/kg reported for a new organic semiconductor. Notebookcheck

-

Module cost: When converted into area or wattage, you might expect something on the order of US$50-200 per m² for the module (excluding installation) in near-term commercial scenarios.

-

Cost per watt: For the very best projected materials, maybe ~US$0.30-1.00/W for the module itself (not installed).

-

Additional factors: Substrate cost, encapsulation, lifetime (how many years before degradation), integration into your system (flexible vs rigid), size/area of implementation.

Organic Solar Cell Working Principle

Organic solar cells (OSCs), also called organic photovoltaics (OPVs), generate electricity using carbon-based semiconductors instead of silicon. Their working principle is similar to conventional solar cells but with important differences due to how organic materials absorb light and move charges.

Below is a clear, technical explanation tailored to your semiconductor and thin-film background.

Organic Solar Cell Working Principle

Organic solar cells rely on photovoltaic conversion in organic semiconducting thin films, typically made of donor and acceptor materials. The process has four major steps:

1. Light Absorption → Exciton Generation

-

Organic semiconductors absorb photons and generate excitons — bound electron–hole pairs.

-

Unlike silicon, these excitons are strongly bound (binding energy ~0.3–1 eV) due to:

-

low dielectric constant of organics (ε ≈ 3–4)

-

molecular structure

-

This means the exciton cannot separate on its own and must reach a donor/acceptor interface.

2. Exciton Diffusion to Interface

-

Excitons diffuse only ~5–20 nm.

-

Therefore the active layer must be extremely thin (~100 nm) and nanostructured.

Modern OPVs use a bulk heterojunction (BHJ):

-

Donor and acceptor materials are mixed to form an interpenetrating network.

-

This creates millions of nanoscale interfaces so excitons can reach a junction before recombining.

3. Charge Separation at Donor–Acceptor Junction

At the donor–acceptor boundary:

-

The donor’s HOMO level donates a hole.

-

The acceptor’s LUMO captures the electron.

This energy offset (ΔE_LUMO or ΔE_HOMO) overcomes the exciton binding energy and splits the exciton into:

-

a free electron in the acceptor

-

a free hole in the donor

This is the key mechanism that differentiates organic from inorganic photovoltaics.

4. Charge Transport and Collection

Separated charges must travel through their respective phases:

-

Electrons move through the acceptor network → cathode

-

Holes move through the donor network → anode

Finally they are collected at electrodes:

-

Anode: usually ITO (Indium Tin Oxide)

-

Cathode: low-work-function metal (Al, Ca/Al, Ag)

Efficient OPVs require:

-

continuous donor pathways for holes

-

continuous acceptor pathways for electrons

-

high mobility materials

-

suppression of recombination

Energy-Level Diagram (Conceptual)

Photon → Exciton → D/A Interface → Electron in Acceptor LUMO → Cathode → Hole in Donor HOMO → Anode

Voltage output (Voc) is approximately:

Voc ≈ (LUMO_acceptor – HOMO_donor) – energy losses

Key Materials

Donors

-

P3HT

-

PTB7

-

PM6

-

PBDB-T

Acceptors

-

PCBM (fullerene acceptors)

-

Non-fullerene acceptors (NFAs) like Y6 — responsible for >18% PCE breakthroughs

Why Organic Solar Cells Work Differently From Silicon

| Feature | Organic Solar Cells | Silicon Solar Cells |

|---|---|---|

| Photogenerated carriers | Excitons | Free e–/h+ pairs |

| Dielectric constant | Low | High |

| Active layer thickness | ~100 nm | ~150–200 μm |

| Charge separation | Requires heterojunction | Built-in junction field |

| Fabrication | Solution-processed, printing | High-temp crystal growth |

Advantages

-

Lightweight and flexible

-

Printable / roll-to-roll manufacturing

-

Low-temperature processing

-

Potential for low-cost large-area production

-

Semi-transparent options

Limitations

-

Lower efficiency than silicon (typical modules ~8–12%)

-

Shorter lifetime (degradation from oxygen, moisture, UV)

- Stability of interfaces and electrodes

Organic vs Silicon vs Perovskite Solar Cells — Comparison Table

| Category | Organic Solar Cells (OPV/OSCs) | Silicon Solar Cells | Perovskite Solar Cells |

|---|---|---|---|

| Typical Efficiency (commercial/small modules) | 8–12% | 18–22% | 15–22% (pilot-scale) |

| Record Lab Efficiency (2024–2025) | ~19–20% | ~26.8% (mono-Si) | ~26–27% (single-junction) |

| Active Layer Thickness | ~100 nm | ~150–200 µm | ~300–800 nm |

| Photocarrier Type | Strongly bound excitons | Free electron–hole pairs | Weakly bound excitons / free carriers |

| Charge Separation Mechanism | Donor–acceptor interface (BHJ) | Built-in junction electric field | Junction field + low exciton binding |

| Material Type | Organic polymers & small molecules (carbon-based) | Inorganic silicon (c-Si or poly-Si) | Metal halide perovskites (e.g., MAPbI₃, FAPbI₃) |

| Manufacturing Method | Solution-processed, printing, low-temp coatings | High-temp furnaces, wafer slicing, high vacuum | Low-temp coating/printing; scalable |

| Scalability | Very high (roll-to-roll, flexible) | Very high (mature industry) | High potential but still emerging |

| Cost per Watt (projected/module only) | $0.30–$1.00/W (not yet mass-produced) | $0.20–$0.40/W | $0.20–$0.30/W (projections) |

| Substrate Options | Plastic, metal foils, glass | Rigid Si wafers only | Glass, flexible films |

| Weight | Ultra-light | Heavy | Light |

| Flexibility | Excellent (bendable, foldable) | None | Good (depending on encapsulation) |

| Lifetime (Operating Stability) | 3–10 years (degrades faster) | 25–30+ years | 5–20 years (improving) |

| Degradation Issues | Oxygen, moisture, UV, morphology | Slow UV/thermal degradation | Moisture, oxygen, heat, ion migration |

| Toxicity Concerns | Low | Low | Lead content in most perovskites |

| Best Use Cases | Lightweight, flexible, wearables, IoT, curved surfaces | Utility-scale, rooftops, long-term energy | High-efficiency low-cost modules, tandem with Si |

| Integration with MEMS/Thin-Film Systems | Excellent (low-temp deposition) | Poor | Good (low-temp) |

Summary — Which Technology is Best Where?

Organic Solar Cells (OPV)

Best for:

-

lightweight, flexible, conformal surfaces

-

printed electronics

-

IoT and low-power MEMS integration

-

semitransparent solar windows

Trade-off: lower efficiency + shorter lifetime.

Silicon Solar Cells

Best for:

-

rooftop installations

-

utility-scale farms

-

any application requiring 25+ years durability

Trade-off: rigid, heavy, expensive to fabricate, not flexible.

Perovskite Solar Cells

Best for:

-

high efficiency at low cost

-

tandem cells (perovskite + Si)

-

next-generation lightweight modules

Trade-off: stability and lead toxicity are still active challenges.