I am interested in your quartz wafers, specifically those with 0.35mm thickness, for Raman spectroscopy applications. Do you have Raman spectra available for these wafers? If so I would appreciate it if you would send those to me.

Helping Researchers With Raman Spectroscopy Substrate Needs

A Phd requested a quote on the following:

Reference #221172 for specs and pricing.

Get Your Quote FAST! Or, Buy Online and Start Researching today!

Silicon Wafer Calibration of Raman Spectra

A laboratory manager requested a quote for the following:

We are interested in one mono-crystalline Si wafer, undoped, [100] orientation, SSP (if possible). Practically, a Si wafer for spectroscopic purposes (calibration of Raman spectra).

UniversityWafer, Inc. quoted

100mm Intrinsic [100] 1,000um ±50um DSP FZ >70,000 ohm-cm SEMI Prime, 1Flat, MCC Lifetime>1,000μs

Reference #303906 for specs and pricing.

What is Raman Spectra?

Raman spectra are graphs that show the intensity of Raman scattering as a function of the energy or wavelength of the scattered light. They provide information about the vibrational and rotational modes of molecules in a sample, which can be used to identify and characterize chemical compounds. Raman spectra are typically obtained by illuminating a sample with a laser and measuring the inelastic scattering of photons using a spectrometer. The resulting spectrum contains peaks at specific energies or wavelengths, corresponding to the vibrational modes of the molecules in the sample. Each peak in the spectrum is associated with a specific vibrational mode, which can be used to identify the molecular structure of the sample. Raman spectra are a powerful tool for chemical analysis and are used in a wide range of applications in fields such as materials science, chemistry, biology, and medicine.

What is Raman Spectroscopy Wavelength Range?

The wavelength range used for Raman spectroscopy typically involves visible light. It spans approximately 200 to 800 nm, though this can vary depending on the specific system being examined and the laser source used.

However, the wavelength range of the observed Raman shift (which is different from the incident light wavelength) usually falls within the wavenumber range of 10 to 4000 cm-1. This range corresponds to energies associated with molecular vibrational transitions, which Raman spectroscopy is often used to study.

ITO Substrates for Raman Spectroscopy

A graduate student requested the following quote:

I am a graduate student for a project that needs a conductive transparent window for Raman spectroscopy. Was interested to see how much a 2.5" x 2.5" x 1/16" ITO glass would cost? Do you offer any other materials and prices for the same size window piece? Some other potential materials of interest are Alumin, Gold, and Graphene. Looking forward to hearing back about pricing and availibity costs as soon as possible!

100 ohm/sq ITO coated glass

Japan display grade

Size:63.5mm x 63.5mm x 1.1mm

Reference #276044 for specs and pricing.

Sapphire Substrates for Raman Spectroscopy

A lab manager requested the following quote:

Please could you quote for the following: Sapphire window/wafer Diameter 3mm ±0.05mm Thickness 0.1mm ±0.05mm λ 532nm and 785nm (Raman spectroscopy) No coating Not critical (please advise what you’re offering): Edge finish Clear Aperture % or size (mm) Chamfer Flatness Parallelism Scratch/Dig.

Reference #263483 for specs and pricing.

Substrate with low Intrinsic Raman Background

A microfluidic engineer requested the following quote:

Our startup is searching for suitable material for our Raman spectroscopy measurements, We are looking for the materials with low intrinsic Raman background signal, could you offer crystalline quartz or CaF2 with dimensions of (111 * 75 mm* 0.25 mm)?

We prefer thickness of quartz around 0.25 or 0.2 mm, and it is very important that is crystalline quartz. If you can't provide this thickness, please let me know the minimum thickness you can manufacture. How long is the lead time? do you have a minimum order quantity? Thank you very much for your consideration in advance.

Reference #261283 for specs and quantity.

What Material Gives No Infrared (IR) or Raman background?

Materials that provide no infrared (IR) or Raman background are typically those that do not absorb in the IR range and are Raman inactive. Such materials are often used as substrates or containers for spectroscopic analysis to avoid interference with the sample signals. Here are some examples:

-

IR Spectroscopy: For IR spectroscopy, materials like calcium fluoride (CaF2) and barium fluoride (BaF2) are often used for windows or lenses since they have no significant IR absorption in many parts of the IR spectrum.

-

Raman Spectroscopy: In Raman spectroscopy, materials like fused silica or quartz are commonly used as they are Raman inactive. This means they do not produce any Raman scattering, which could interfere with the analysis of the sample.

Reference #114554 for specs and pricing.

Pure Silicon for Raman Spectroscopy

A PhD candidate requested the following quote:

I need one small sample of pure silicon for use as Raman spectroscopy reference. The size requirement is only so that it will fit on a standard microscope slide. I do not have any requirements for the electrical properties or thickness. Please contact me by email with the quote.

We really don't need anything else. We are looking for just a small cheap sample of silicon to adjust the wave shift of our system. We do not have any requirements other than it being a silicon sample with one polished surface that is small enough to mount to a glass slide. Do you think you would be able to help us out?

Reference #132481 for specs and quantity.

Graphene Documentation

A Senior Researcher requested help with the following:

Question:

Which type of documentation for single/bi-/tri- layer graphene do you have? Optical microscopy, Raman spectroscopy, TEM or other? Is the graphene continuous films?

Answer:

We can do the following:

- Monolayer Graphene 10mm x 10mm on SiO2/Si 12.5mm x 12.5mm (fully covered) Pack 4 units

- Monolayer Graphene on Your Substrate

- Monolayer Graphene on SiO2/Si (4" wafer) fully covered

- Bilayer Graphene film on SiO2/Si 10mm x 10mm (non AB Bernal stacking)

We do optical microscopy and Raman per batch. We can offer Specific Raman on film for additional cost.

Reference #156446 for specs and quantity.

Float Zone Silicon for Raman Spectral Calibration

A corporate scientist requested the following quote:

These wafers used for Raman spectral calibration. Need 10 for now. Thckness not critical except for handling.

Item #143625

25.4mm Undoped <100> FZ >1,000 ohm-cm 500um SSP

Fused Silica for Conducting Raman Spectroscopy of Thin Films

A process chemist requested a quote for the following:

I am interested in fused silica wafers. I need to do Raman spectroscopy of thin films deposited on fused silica (or on a substrate which doesn"t show Raman peaks). Please give a price list for all three types of fused silica substrates that you have.

Refrence # 209272 for specs and pricing.

What is Raman Spectroscopy?

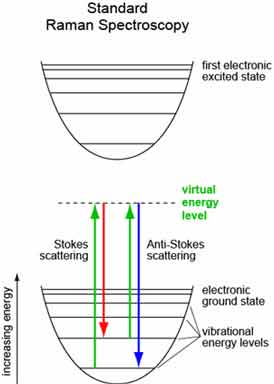

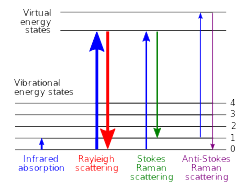

The Raman effect is a form of inelastic light scattering, resulting from vibrational excitations of a molecule (see the figure below). When a sample is illuminated with a monochromatic laser light, some of the molecular vibrations will be scattered at frequencies different from the incident frequency, or color. These frequencies are unique to the type of molecules and types of bonds they contain, which is why a Raman spectrum can identify the molecules present in a sample.

(see the figure below). When a sample is illuminated with a monochromatic laser light, some of the molecular vibrations will be scattered at frequencies different from the incident frequency, or color. These frequencies are unique to the type of molecules and types of bonds they contain, which is why a Raman spectrum can identify the molecules present in a sample.

Raman spectroscopy uses a laser to excite the vibrational modes of a sample, and a photomultiplier to detect these frequencies as light is scattered from the sample. Usually, the laser beam is focused on a specific layer of interest to avoid unwanted interference from other layers. Typical Raman spectra are recorded at a fixed wavelength, such as visible or near-infrared, although FT-Raman can use lasers with longer wavelengths for greater sensitivity.

Raman spectroscopy has numerous applications in (bio)chemistry and solid-state physics, for example analyzing crystallinity or the diameter of single or multi-walled carbon nanotubes. The technique is non-destructive and can be applied to gaseous, liquid, or solid-state samples. Raman spectroscopy is also an important tool in forensic science, for example identifying trace evidence from a crime scene. The technique can also provide useful information about the structure of a metal compound by investigating the metal-ligand bond, and it can help identify organic molecules by analyzing functional groups and their fingerprints.

How Does Raman Spectroscopy Work?

When light interacts with materials, the vast majority of photons disperse at their original frequency (called elastic scattering). However a very small fraction of photons are scattered with a different frequency, which is called inelastic scattering or Raman scattering. C V Raman discovered this effect and won the 1930 physics Nobel Prize for it.

elastic scattering). However a very small fraction of photons are scattered with a different frequency, which is called inelastic scattering or Raman scattering. C V Raman discovered this effect and won the 1930 physics Nobel Prize for it.

Inelastic Scattering of Light

The chemistry of Raman spectroscopy is based upon inelastic scattering of monochromatic light, typically from lasers in the visible, near infrared and near ultraviolet range, by vibrations and phonons in molecules. This causes a change in the energy of photons of the laser radiation that is detected by the instrument, which can be measured as a shift in wavelength. The change in energy gives information about the vibrational modes of the molecules that are detected, much like IR spectroscopy.

Unlike elastic (Rayleigh) scattering, the vibrations that cause Raman scattering are largely localized within the molecule. Consequently, the resulting scattered photons have less overall energy and are thus more sensitive to molecular vibrations. This gives a molecular fingerprint, or chemical profile, of the sample that can be used to determine its composition and structure.

A sample's Raman spectrum is often very broad with many peaks due to the fact that the vibrational modes of most molecules involve many different bonds and vibrational energies. This sensitivity makes the method ideal for analyzing samples containing many different chemicals. It also allows identification of a sample's molecular structure even when the sample is a gas.

In contrast to infrared spectroscopy, which requires molecular vibrations that are excited at lower energy levels, Raman spectroscopy can detect vibrations at higher levels. As a result, it is often possible to identify organic molecules using Raman spectroscopy, which are very difficult to identify with IR spectroscopy.

Molecular Vibrations

When a molecule absorbs light it can vibrate at a frequency that's unique to the molecule and type of bond. If this happens then some of the absorbed energy will be scattered outward at a different frequency and color from the original beam. This is called inelastic scattering or Raman effect and it was discovered by Sir C.V. Raman in 1930. The frequencies of the scattered light can tell us which molecules are present in the sample and about their structure.

To perform Raman spectroscopy the sample is illuminated with monochromatic visible radiation. The absorbed energy creates a virtual state in the electron cloud of a molecule that has the same momentum as its ground electronic state. A portion of this energy is used to excite a vibrational or rotational mode in the molecule and the remainder is emitted as a photon with reduced energy. This emitted photon is known as a Raman photon.

The vibrational modes that are detected by Raman spectroscopy are related to the changing polarizability of a molecule. For a molecule to be Raman active there must be a change in the polarizability when the molecule absorbs the radiation. A simple example is carbon dioxide. The symmetric stretch vibration is Raman active but the asymmetric bend (infrared) is not.

Photons

Raman spectroscopy is a non-destructive analytical technique based on the inelastic scattering of photons from vibrational modes (although rotational and other low frequency modes may be observed). The energy of the scattered photons is shifted, providing valuable information about molecular structure. Raman spectroscopy is named after Indian physicist C V Raman who first described the scattering phenomenon in 1928. It is commonly used in chemistry to provide a structural fingerprint by which molecules can be identified.

In a typical Raman experiment, a monochromatic laser in the visible, near infrared or even ultraviolet wavelengths is used as the excitation source. This interacts with atomic and molecular vibrations, or phonons, which cause the photons’ energy to be shifted up or down. The resulting Raman spectrum can be analyzed to give valuable information about the vibrational modes of the molecules involved, as well as other physical properties such as molecular bond lengths and vibrational frequencies.

The intensity of the Raman signal is related to the polarizability of the molecule. Molecules with a small permanent dipole moment tend to be Raman active, while those with large dipole moments do not. Hence, for a given chemical system, the vibrational features accessible by Raman spectroscopy are typically different from those accessed by IR spectroscopy.

Because of this, the sensitivity of Raman spectra is often greater than that of IR spectra. This allows for detection of vibrational features in liquids and gases that would be impossible or at least extremely difficult to observe with IR instruments.

Detectors

When light strikes a molecule, some of it is scattered away with a loss or gain of energy, resulting in vibrations that can be detected. The frequencies of the scattering light are unique to the molecule and type of bonds it contains, so the Raman spectrum provides valuable information about the chemical structure of a sample.

To collect a Raman spectrum, a monochromatic laser at a specific wavelength is used to illuminate the sample. The majority of the photons are scattered without any change in energy (Rayleigh scattering), but a small proportion lose or gain energy to molecular vibrations. These vibrations can then be detected by sensitive detectors to produce a detailed, information-rich spectral fingerprint of the sample.

Raman spectroscopy works well for samples in solid, liquid or gaseous form and can be used to answer qualitative and quantitative analytical questions. It is a powerful tool for characterizing materials and can be applied to a broad range of industrial applications.

One of the most popular applications of Raman spectroscopy is in forensics and archaeology. For example, a Raman spectrum can help identify the paints and pigments in paintings and other cultural artifacts. IRUG's comprehensive, rigorously peer-reviewed online database of spectra is available for use by researchers and conservators worldwide. In addition to its ability to determine the chemical composition of a sample, Raman spectroscopy can also detect polymorphic forms of a material, such as sintering and solidification.

How are Silicon Substrates Used With Raman Spectroscopy?

Silicon is a common substrate material in Raman spectroscopy because it is optically transparent and has a low Raman scattering cross-section, which minimizes background noise in the Raman spectra. Additionally, silicon substrates are often coated with a thin layer of silicon dioxide (SiO2), which provides a smooth and flat surface for the sample to be analyzed. The SiO2 layer also enhances the Raman signal by creating a surface-enhanced Raman scattering (SERS) effect.

What other Substrates Work Well with Raman Spectroscopy?

The choice of substrate material for Raman spectroscopy depends on the nature of the sample and the experimental conditions. Silicon is a commonly used substrate for Raman spectroscopy due to its low Raman scattering cross-section and high optical transparency. Other materials such as glass, quartz, and sapphire can also be used as substrates, depending on the specific application. The thickness and roughness of the substrate can also affect the Raman signal intensity, so it is important to choose a substrate with a suitable thickness and surface quality. In some cases, special substrates, such as those with nanostructured surfaces, can be used to enhance the Raman signal through surface-enhanced Raman scattering (SERS). Ultimately, the choice of substrate material and specifications should be optimized for the specific sample and experimental conditions to obtain the best results.

What are Raman Spectrometer Certified Reference Standard?

Raman spectrometer certified reference standards are high-quality samples that have been extensively characterized and certified for use in calibrating and validating Raman spectrometers. These standards are typically used to ensure that Raman instruments are working accurately and producing consistent results over time.

Certified reference standards for Raman spectroscopy can include a range of materials, such as inorganic compounds, organic compounds, and polymers. They are typically characterized using multiple analytical techniques, such as X-ray diffraction, infrared spectroscopy, and thermal analysis, to ensure their purity and structural integrity. The standards are then analyzed using a Raman spectrometer under controlled conditions to establish their Raman spectra and validate the performance of the instrument.

Raman spectrometer certified reference standards are important for ensuring the accuracy and reliability of Raman spectroscopy measurements, and are used in a wide range of applications, including pharmaceuticals, biomedical research, forensics, and materials science.

Raman Spectrometer Certified Reference Standard

A government researcher asked for the following:

I am looking for a raman spectrometer certified reference standard. I prefer a Si wafer. Do you have any that would suffice and are certified for QA purposes?

Refrence #225404 for specs and pricing.

What is a Raman Spectrometer?

A Raman spectrometer is an instrument that uses Raman spectroscopy to analyze the vibrational and rotational modes of molecules in a sample. It works by illuminating a sample with a laser and measuring the inelastic scattering of photons as the laser light interacts with the sample. The scattered photons are then collected and analyzed using a spectrometer to generate a Raman spectrum, which provides information about the chemical composition and molecular structure of the sample.

A Raman spectrometer typically consists of several components, including a laser source, a sample holder, a microscope or other optics for focusing the laser light onto the sample, and a spectrometer for collecting and analyzing the scattered photons. Raman spectrometers can be configured in a variety of ways, depending on the specific application and sample requirements.

Raman spectrometers are widely used in a range of fields, including materials science, chemistry, biology, and medicine, for applications such as chemical analysis, quality control, and characterization of materials. They are a powerful analytical tool that can provide detailed information about the chemical and structural properties of a wide range of materials.

Silicon Wafers Used as Blank Sample for Raman Spectroscopy

A graduate student requested the following quote:

Question:

I am contacting you to ask for product recommendation for silicon wafer. I am looking for a wafer to be used as a blank sample for Raman spectroscopy. In the university wafer website, there are to be lots of options (single polished, double polished, undoped, etc.) for wafers, so could you recommend a suitable silicon wafer for Raman spectroscopy?

Answer:

What materials are effective for Raman?

Raman spectroscopy is based on the principle that an excitation source can induce changes in the electric dipole in relation to the vibrational and rotational states of the analyte. More simply, unlike infrared spectroscopy, which requires a simple dipole moment, Raman relaxation is based on the principle that an excitation source can induce a dipole within the analyte. Typically, covalent bonding is required to observe Raman signals. In contrast to transitions such as C-O or O-H, transitions such as C=C, C-C or C-H are generally intense in Raman spectroscopy, following the mutual exclusion rules of infrared spectroscopy. Rotational and vibrational transitions, which are often large in Raman spectroscopy, are generally weak in infrared spectroscopy (and vice versa).

Organic substances such as raw drugs, organic solvents, polymers, hazardous drugs, explosives, etc.

Polyatomic minerals such as magnesium sulfate, sodium bicarbonate, titanium dioxide, and calcium phosphate

Molecules containing only single bonds: C-C, C-H, or C-O (e.g. aliphatics, sugars, starch, cellulose)

Highly polar small molecules such as ethanol

Substances without covalent bonds: pure ionic species (e.g. NaCl, KCl)

Highly fluorescent samples such as vegetable matter

Black and dark-colored samples that can completely absorb laser light

Any substance with a weak Raman signal within the region being examined (e.g. water in the region 200 to 2,000 cm-1)

Most metals and elemental substances

Reference #279279 for specs and pricing.

Understanding Raman Spectroscopy for Material Analysis

Raman spectroscopy is a powerful tool that helps scientists understand the makeup of different materials at the molecular level. It's like having a super-powerful microscope that can see how atoms and molecules move and interact inside various substances. This technique doesn't damage the materials being studied and has changed how we analyze materials in many areas of science. Let's explore how this amazing method works and why it's so important for studying materials in different fields.

Key Takeaways

- Raman spectroscopy analyzes scattered light from molecules, giving detailed information about chemical structure and composition

- It uses laser light to excite molecules and measure energy changes, with three types of scattering: Rayleigh, Stokes, and Anti-Stokes

- The technique can detect very small changes in molecular structure and is useful for analyzing solids, liquids, and gases with minimal sample preparation

- Raman spectroscopy has wide-ranging applications in materials science, biology, pharmaceuticals, and geology

- Advanced versions like Surface-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy (SERS) can detect single molecules, making it even more sensitive and useful

- Challenges include weak signals and fluorescence interference, but researchers are working on solving these issues

- Future developments aim to make Raman devices more portable and accessible for real-time material analysis

What is Raman Spectroscopy?

Raman spectroscopy is a method of examining materials using light interaction. When a special laser is shone on a sample, the light interacts with the molecules in the material, causing it to scatter in a unique pattern. This scattered light tells us a lot about the material's structure, what it's made of, and how its molecules interact. The technique is named after Sir C.V. Raman, who discovered this effect in 1928 and won the Nobel Prize for it in 1930.

One of the best things about Raman spectroscopy is that it doesn't destroy the sample. This means scientists can study all kinds of materials, even delicate ones like old artifacts, living tissues, or rare minerals, without damaging them. Raman spectroscopy can analyze solids, liquids, and gases, making it really useful in many areas of science. From studying rocks and minerals in geology to looking at the structure of medicines, Raman spectroscopy helps us understand the material world around us in amazing detail.

How Does Raman Spectroscopy Work?

The main idea behind Raman spectroscopy is how light interacts with matter at the molecular level. When laser light hits a material, most of the light bounces off without changing. This is called Rayleigh scattering. But a small amount of the light - about one in every million photons - interacts with the molecules in a special way, leading to a change in the light's energy. This change is the key to understanding the material's molecular secrets.

There are three main types of light scattering in the Raman effect:

- Rayleigh scattering: The most common type, where light bounces off without changing energy. It doesn't tell us about the material's structure.

- Stokes scattering: The scattered light loses a bit of energy to the molecule, resulting in a longer wavelength.

- Anti-Stokes scattering: The scattered light gains a bit of energy from the molecule, shifting to a shorter wavelength.

Scientists mainly look at the Stokes and Anti-Stokes scattering patterns because these energy shifts are directly related to how the molecules in the sample vibrate. Each material has a unique set of vibrations, creating a special Raman spectrum - like a molecular fingerprint that can identify and describe the substance. The strength and position of the peaks in a Raman spectrum tell us about the chemical bonds, molecular shape, and crystal structure of the material being studied.

What Can We Learn from Raman Spectroscopy?

Raman spectroscopy gives us lots of information about materials:

- Chemical composition: It can identify specific molecules and compounds in a sample.

- Molecular structure and chemical bonds: It shows how atoms are connected within molecules.

- Crystal structure and polymorphism: It can tell different crystal structures of the same chemical compound apart.

- Impurities and defects: Even tiny amounts of impurities or structural problems can be detected.

- Phase transitions and environmental effects: Changes due to temperature, pressure, or other factors can be studied.

- Molecular orientation and alignment: Sometimes, it can show how molecules are positioned within a material.

This wealth of information makes Raman spectroscopy valuable in many industries and research areas. For example, semiconductor manufacturers use it to check the quality and purity of their materials, looking for defects that could affect how devices work. Geologists use it to study what rocks and minerals are made of, helping them understand Earth's history. In art conservation, it helps analyze pigments in paintings without damaging them, which is useful for authenticating art and figuring out how to preserve it.

Advanced Raman Techniques

Scientists have developed more advanced versions of Raman spectroscopy to make it even more powerful. These techniques enhance sensitivity, spatial resolution, and expand application scope:

Surface-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy (SERS)

SERS makes Raman spectroscopy much more sensitive. It uses special surfaces, usually made of tiny structures of metals like gold or silver. When molecules stick to these surfaces, the Raman signal becomes much stronger - sometimes amplified by up to 1011 times, enabling single-molecule detection.

Key applications include:

- Trace detection of explosives and drugs in forensic science

- Analysis of microplastics and nanomaterials in environmental monitoring

- Medical diagnostics for spotting early signs of diseases

The major advantage of SERS is its ability to work with extremely low-concentration samples, making it invaluable for detecting substances present in minute quantities.

Tip-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy (TERS)

TERS combines Raman spectroscopy with a very fine metal tip, similar to those used in atomic force microscopy (AFM) or scanning tunneling microscopy (STM). This allows scientists to get Raman information from extremely small areas - with resolution down to 20-30 nanometers, effectively overcoming the diffraction limits of traditional microscopy.

TERS excels in:

- Nanoscale chemical mapping of surfaces

- Studying crystal defects and semiconductor heterostructures

- Analyzing photodetectors and other nanoscale electronic devices

This technique helps scientists understand how chemical makeup and structure of materials change at very small scales, which often determines their overall performance characteristics.

Spatially Offset Raman Spectroscopy (SORS)

SORS represents a significant breakthrough for analyzing subsurface layers. It works by collecting Raman signals from deeper layers by offsetting the detection point from the laser excitation spot.

SORS is particularly valuable for:

- Non-destructive analysis of packaged pharmaceuticals

- Examining biological tissues beneath the surface

- Analyzing materials through opaque containers

The primary advantage of SORS is its ability to penetrate opaque materials without any sample preparation, preserving the integrity of the analyzed substance.

Hyperspectral Raman Imaging

This technique generates detailed chemical maps by collecting full spectra at each pixel, enabling sophisticated multivariate analysis. It creates a comprehensive visualization of chemical distribution across a sample.

Applications include:

- Mapping polymorph distribution in pharmaceutical formulations

- Studying stress and strain patterns in materials

- Analyzing heterogeneous samples with multiple components

Hyperspectral Raman imaging excels at resolving chemically similar components while providing valuable spatial context for understanding material properties.

Resonance Raman Spectroscopy

This enhancement technique uses laser wavelengths that match the electronic transitions of the target analyte, selectively enhancing specific vibrational modes. This provides greater sensitivity for particular molecular structures.

Resonance Raman is particularly useful for:

- Studying photosynthetic pigments

- Analyzing conjugated polymers

- Examining materials with strong chromophores

The technique increases selectivity for target molecules, making it easier to study specific components within complex mixtures.

Advanced Preprocessing and Analysis

Modern Raman spectroscopy leverages sophisticated data processing techniques to extract maximum information from collected spectra:

- Baseline correction and noise reduction algorithms improve signal quality

- Machine learning algorithms automate spectral interpretation

- Advanced statistical methods enhance pattern recognition

These computational approaches significantly improve signal-to-noise ratios and enable automated chemical identification, even in complex mixtures.

Key Advancements in Instrumentation

The evolution of Raman technology has been driven by improvements in several critical hardware components:

- High-sensitivity CCD arrays and FT-Raman systems for rapid measurements

- Holographic notch filters that efficiently reject laser light

- Automation systems that integrate with process control for real-time industrial monitoring

These advanced techniques have greatly expanded what Raman spectroscopy can do, allowing researchers to study materials in unprecedented detail. For example, in nanotechnology, TERS can examine individual nanostructures or map different chemical species across a surface with nanometer precision. This level of detail is crucial for developing and improving nanoscale devices like advanced photodetectors, where subtle variations in composition or structure can dramatically affect performance characteristics.

The combination of these enhanced techniques is revolutionizing fields like materials science, biotechnology, and environmental monitoring by offering non-destructive, label-free analysis with extraordinary sensitivity and spatial resolution.

Applications of Raman Spectroscopy

Raman spectroscopy is used in many different scientific fields and industries:

- Materials Science: Studying new materials for technology and understanding how materials behave

- Biology: Examining cells and tissues without damaging them to study changes and treatments

- Pharmaceuticals: Checking drug quality, purity, and making sure the ingredients are correct

- Geology: Analyzing rocks and minerals for geological studies

In materials science, Raman spectroscopy helps develop new materials. It allows scientists to understand the structure, composition, and behavior of materials under different conditions. This knowledge is important for creating things like more efficient solar panels, stronger and lighter building materials, and new electronic components. For example, when developing new semiconductors, Raman spectroscopy can show the quality of crystals, strain, and defects, which all affect how well electronic devices work.

Biologists use Raman spectroscopy to study living cells and tissues without needing to stain or prepare them in ways that might change them. This lets researchers watch cellular processes happening in real-time, see how cells change during diseases, and study how different treatments affect cells at the molecular level. In cancer research, for instance, Raman spectroscopy can tell the difference between healthy and cancerous tissues based on small changes in their molecular makeup, which could lead to better ways of diagnosing cancer.

The pharmaceutical industry uses Raman spectroscopy a lot for quality control and monitoring how drugs are made. It can quickly check if drug compounds are what they're supposed to be and if they're pure. It can also detect fake medications and make sure the active ingredients in drugs are in the right form. During drug development, it helps scientists understand how different formulations affect how stable and effective a drug is. It's also used to monitor drug manufacturing in real-time, ensuring consistency and quality in production.

Challenges and Future of Raman Spectroscopy

While Raman spectroscopy is very useful, it does face some challenges:

- Weak Signals: The Raman effect is naturally weak, which can make it hard to detect, especially in samples with low concentrations.

- Fluorescence Interference: Some materials glow strongly when excited by the laser, which can overpower the Raman signal.

- Complex Data: Raman spectra of complicated mixtures or unknown samples can be hard to interpret.

- Sample Heating: Strong lasers used to improve the signal can sometimes heat up the sample, potentially changing or damaging it.

- Depth Limitation: Traditional Raman spectroscopy mainly works on or near the surface of materials.

Scientists and engineers are working on several ways to overcome these challenges:

- Developing more sensitive detectors and better lasers to improve signal detection and reduce the time needed for measurements.

- Using advanced data processing, including machine learning and artificial intelligence, to better interpret complex spectra.

- Combining Raman spectroscopy with other analytical techniques to get more complete information.

- Exploring new ways to prepare samples and new materials to enhance Raman signals and reduce interference.

The future of Raman spectroscopy looks very promising. Scientists are making Raman systems smaller, using technologies like silicon photosensors, to create portable Raman devices. These compact instruments could revolutionize on-site material analysis in fields like environmental monitoring, art conservation, and forensic science.

Researchers are also combining Raman spectroscopy with other new technologies. For example, using Raman spectroscopy with microfluidic devices allows real-time monitoring of chemical reactions and biological processes at very small scales. In medical diagnostics, scientists are exploring the use of fiber-optic Raman probes for analyzing tissues inside the body, which could lead to new ways of detecting and monitoring diseases without invasive procedures.

Conclusion

Raman spectroscopy shows us how powerful the interaction between light and matter can be in revealing the complex world of materials at the molecular level. From its beginnings as an interesting optical effect to its current status as an essential analytical tool, Raman spectroscopy has transformed our ability to study and understand the material world around us.

As we continue to improve Raman spectroscopy, we're discovering new things about the basic properties of materials, driving innovation across many scientific and technological fields. The ongoing improvements in sensitivity, resolution, and data analysis are helping us tackle more complex challenges, from developing new materials for clean energy to understanding the molecular basis of diseases.

Whether you're a student just starting in science, an experienced researcher, or simply someone fascinated by the wonders of the material world, Raman spectroscopy offers a window into a world of discovery that keeps expanding. It reminds us that in the interaction of light and matter, there are always new stories to uncover, new mysteries to solve, and new frontiers to explore. Looking ahead, the continued development of Raman spectroscopy will play a crucial role in addressing some of our biggest challenges, from environmental sustainability to human health, showing the lasting power of scientific inquiry and technological innovation.