Essential Silicon Wafer Etching Techniques

- Wet etching uses chemical solutions like KOH and BOE for cost-effective material removal

- Dry etching techniques including RIE offer superior precision for advanced applications

- Temperature control and proper chemical concentrations are critical for consistent results

- Selection between isotropic and anisotropic etching depends on specific application needs

- Safety protocols are essential when handling hazardous etching chemicals

- Quality control metrics include etch rate, uniformity, selectivity, and surface finish

Get Your Quote FAST! Buy Online and Start Researching Today!

Related Silicon Wafer Etching Methods and Process Resources

- Wet Etching

- KOH Etching of Silicon Wafers

- Dry Etching

- Reactive Ion Etching (RIE) Preparation Guide

- Deep Reactive Ion Etching (DRIE)

- Silicon Etching Chemicals and Etchants

- Anisotropic Wet Etching

- Silicon Wafer Crystal Orientation (100/110/111)

- Silicon Wafers

- Etched Silicon Wafers

Introduction to Silicon Wafer Etching

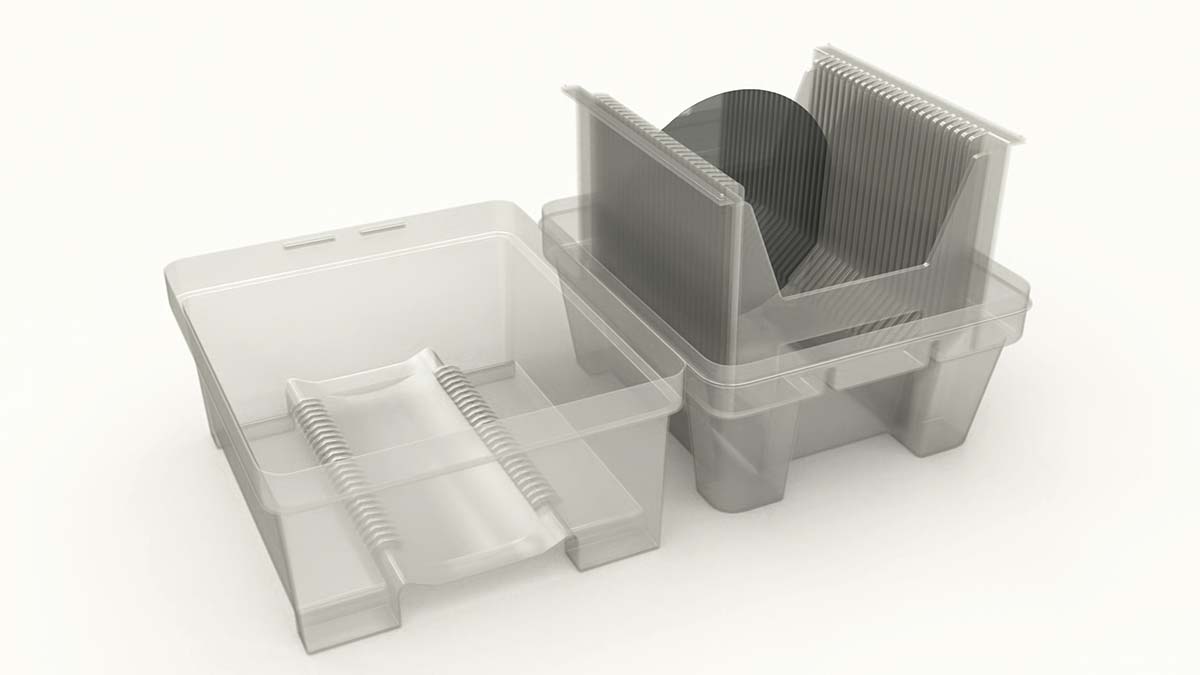

Silicon wafer etching is a basic process in making computer chips. It involves removing material from silicon wafers to create patterns and structures. This is a key step in making integrated circuits, MEMS devices, and other electronic parts. The etching method you choose affects how well your device works, how reliable it is, and how many good chips you can make.

There are two main types of etching: wet and dry. Wet etching uses liquid chemicals to dissolve unwanted silicon, while dry etching uses plasma or gases. You need to pick the right method based on how small your features need to be, their shape, and what materials you're working with. Wafer processing companies offer different etching options for different projects.

In this guide, we'll look at the best ways to etch silicon wafers. You'll learn how to get better results, check quality, and what new trends are coming. Whether you're doing research with small wafers or making products with bigger ones, understanding these methods will help you do better work with silicon.

Understanding Silicon Wafer Properties

Before we talk about etching methods, it's important to understand silicon wafers themselves. The crystal structure, orientation, and doping of silicon affect how it etches. These properties determine etch rates, shapes, and surface quality after etching.

Silicon wafers come in different crystal orientations, usually labeled as (100), (110), and (111). Each orientation etches differently with specific chemicals. For example, with potassium hydroxide (KOH), (100) oriented wafers etch faster than (111) oriented surfaces, creating V-shaped grooves with 54.7° sidewalls. This is useful for making precise structures in MEMS devices and other special applications. By understanding these crystal effects, engineers can control the shapes and sizes of features during etching.

The type and amount of dopants in silicon wafers also affect etching. Heavily doped regions usually etch at different rates than lightly doped or pure silicon. For instance, p-type (boron-doped) silicon typically etches more slowly than undoped silicon in certain chemicals, while n-type (phosphorus or arsenic-doped) silicon might etch faster in some solutions. This property is often used to create selective etching patterns or to use heavily doped regions as etch stops. The dopant concentration can change etch rates by up to 10 times in some cases.

Surface finish and preparation before etching also matter. Wafers usually go through thorough cleaning to remove dirt that could cause uneven etching. Common cleaning methods include RCA cleaning (removing organic contaminants, thin oxide layers, and ionic contamination), Piranha cleaning (H₂SO₄:H₂O₂ mixture for organic residues), and HF dipping (removing native oxide layers right before etching). Good preparation ensures consistent results and prevents defects. Even tiny contaminants can act as micro-masks, creating unwanted features or rough surfaces.

Wet Etching Techniques for Silicon Wafers

Wet etching is one of the most common ways to process silicon wafers because it's simple, cheap, and fast. This method involves putting silicon wafers in liquid chemicals that react with the surface to remove material. Wet etching can be isotropic (etching evenly in all directions) or anisotropic (etching more in certain directions), depending on the chemical used and the crystal structure of the silicon. You choose between these approaches based on what you need for your application and what shapes you want.

Potassium hydroxide (KOH) etching is one of the most common anisotropic wet etching methods for silicon. This alkaline chemical etches different crystal planes at different rates, making it great for creating precise microstructures. Typical KOH etching uses 20-40% concentration in water at temperatures of 60-85°C, achieving etch rates of 0.5-1.5 μm/min for (100) silicon at 80°C. KOH etching works well for creating V-grooves, pyramid structures, and microchannels in silicon wafers. The etch rate difference between {100} and {111} planes can be more than 100:1, allowing for very precise geometric structures.

Tetramethylammonium hydroxide (TMAH) is another option for anisotropic silicon etching with several advantages. Unlike KOH, which contains potassium ions that can contaminate devices, TMAH is compatible with CMOS processes. It also works well with silicon dioxide and silicon nitride masks. Typical TMAH etching uses 20-25% concentration in water at temperatures of 70-90°C, achieving etch rates of 0.5-1 μm/min for (100) silicon. TMAH often produces smoother surfaces than KOH and is preferred for final device fabrication in industry. It's also less toxic than other chemicals and can be handled more safely, making it popular in research and production environments concerned with safety and environmental impact.

Hydrofluoric acid (HF) based solutions are important in silicon wafer processing, mainly for etching silicon dioxide rather than silicon itself. Buffered Oxide Etch (BOE), made of HF diluted with ammonium fluoride (NH₄F), provides controlled etching of SiO₂ layers with better stability and safety. For silicon etching, mixtures of HF and nitric acid (HNO₃), sometimes called "HNA" when water is added, provide fast and uniform material removal. These isotropic etchants are valuable for applications needing smooth surfaces or rapid material removal. The HNA system works through a two-step process where HNO₃ oxidizes the silicon surface, and HF then dissolves the oxide layer, with etch rates that can exceed 50 μm/min under optimized conditions.

Dry Etching Technologies for Advanced Applications

Dry etching technologies have become more important for advanced silicon wafer processing, especially as features get smaller and aspect ratios increase. These techniques use plasma or vapor-phase reactants instead of liquid chemicals to remove material from silicon surfaces, offering better control over etch profiles and feature dimensions. Dry etching has changed semiconductor manufacturing by enabling the creation of nanoscale features with precise shapes that would be impossible with traditional wet etching methods.

Reactive Ion Etching (RIE) combines physical ion bombardment with chemical reactions to achieve highly directional etching profiles. In a typical RIE system, process gases are introduced into a vacuum chamber where RF power creates a plasma, generating reactive species and ions. These ions are accelerated toward the wafer surface by an electric field, resulting in combined chemical and physical processes that remove material. RIE offers excellent anisotropy for creating high-aspect-ratio features, good control over etch profiles, and the ability to etch features smaller than 100 nm. Common gas mixtures for silicon RIE include SF₆/O₂ for high etch rates and CF₄/O₂ for more controlled etching. Process parameters such as RF power, pressure, gas flow rates, and substrate temperature can be adjusted to optimize etch characteristics for specific applications.

Deep Reactive Ion Etching (DRIE) is a special form of RIE designed for creating extremely deep, high-aspect-ratio structures in silicon. The most common DRIE approach is the Bosch process, which alternates between etching steps using SF₆ plasma and passivation steps using C₄F₈ plasma that deposits a protective polymer on sidewalls. This cyclic process creates "scalloped" sidewalls but enables structures with aspect ratios exceeding 50:1 and depths of hundreds of microns. DRIE has revolutionized MEMS fabrication, enabling devices such as inertial sensors with deep proof masses, through-silicon vias (TSVs) for 3D integration, and microfluidic channels with vertical sidewalls. Recent advances in DRIE technology have focused on reducing scalloping effects and improving sidewall smoothness.

Inductively Coupled Plasma (ICP) etching systems use an inductively coupled plasma source to generate high-density plasmas at low pressures. These systems offer higher plasma densities than standard RIE (10¹¹-10¹² ions/cm³), independent control of ion energy and plasma density, reduced damage to sensitive devices, and higher etch rates while maintaining anisotropy. ICP etching is particularly valuable for etching thick silicon layers efficiently while maintaining excellent profile control. ICP systems typically use two RF power sources: one to generate the plasma (ICP power) and another to control ion energy at the substrate (bias power). This setup provides great flexibility in process optimization, enabling the creation of sophisticated structures with minimal damage to the underlying material.

Advanced Masking Techniques for Precision Etching

The success of any silicon etching process depends a lot on the quality and durability of the masking materials used. Advanced masking techniques enable precise pattern transfer and protection of regions that should remain unetched during the etching process. The choice of mask material depends on the etching method, the desired feature size, and the depth of etching required. Masking technology has improved significantly over the years, with new materials and deposition methods being developed to meet the demands of increasingly complex device fabrication.

Thermal silicon dioxide (SiO₂) remains one of the most widely used masking materials for silicon etching, particularly for wet etching processes. It offers excellent resistance to KOH and TMAH with selectivity ratios exceeding 100:1, meaning the silicon etches at least 100 times faster than the oxide mask. Silicon dioxide can be precisely patterned using standard photolithography and HF-based etching, and it can be thermally grown or deposited using PECVD or LPCVD techniques. Typical mask thicknesses range from 100 nm to 2 μm depending on the required etch depth. Thermal oxide silicon wafers provide ready-to-use substrates with high-quality SiO₂ layers optimized for masking applications. The thermal oxidation process creates a dense, pinhole-free oxide that provides superior masking performance compared to deposited oxides, particularly for extended etching processes where mask integrity is critical.

Silicon nitride (Si₃N₄) offers better etch resistance compared to silicon dioxide for many applications, particularly in KOH etching where selectivity ratios can exceed 1000:1. This exceptional durability makes silicon nitride the mask of choice for deep etching processes in KOH and other aggressive etchants. Silicon nitride is typically deposited using LPCVD for highest quality, though it is harder to pattern than SiO₂, usually requiring hot phosphoric acid etching. Low-stress silicon nitride is particularly valuable for applications requiring minimal wafer warping during processing. The exceptional chemical stability of silicon nitride makes it an ideal masking material for extended etching processes, while its mechanical strength allows it to withstand the stresses associated with deep etching without cracking or peeling off.

For particularly demanding etching processes, combinations of masking materials may be used. SiO₂/Si₃N₄ stacks provide enhanced durability, while metal masks such as chromium or aluminum may be used for specialized dry etching applications. Polysilicon hard masks can also be useful for specific process flows. These composite masking approaches allow for optimization of both pattern transfer fidelity and etch resistance. The selection of appropriate mask materials and thicknesses depends on specific process requirements, including etch depth, etchant composition, and temperature. Advanced masking strategies often involve multi-layer stacks where each layer serves a specific purpose in the overall process flow, such as adhesion promotion, stress compensation, or enhanced etch resistance.

Process Optimization and Control

Getting consistent, high-quality etching results requires careful optimization and control of process parameters. Changes in temperature, concentration, agitation, and other factors can significantly impact etch rates, uniformity, and surface quality. Proper process control is essential for reproducible results, particularly in research and production environments. The development of robust process control methodologies has become increasingly important as device dimensions shrink and performance requirements become more stringent.

Temperature has a big effect on etch rates, with most wet etching processes following Arrhenius behavior where etch rates typically double with every 10°C increase in temperature. While higher temperatures generally increase etch rates, they may reduce selectivity and introduce other challenges. Temperature differences across wafers can cause uneven etching, leading to inconsistent feature dimensions. For critical etching processes, temperature-controlled baths with circulation systems ensure uniform heating and consistent results. In dry etching systems, substrate temperature control through helium backside cooling or other mechanisms helps maintain process stability and reproducibility. Advanced temperature control systems often use PID (Proportional-Integral-Derivative) controllers with multiple temperature sensors to ensure uniform conditions across the entire process chamber or bath, with temperature stability of ±0.1°C or better for critical applications.

For wet etching processes, maintaining consistent etchant concentration is crucial for reproducible results. Etchant depletion occurs during processing, gradually reducing etch rates, while evaporation can increase the concentration of non-volatile components. Water absorption from air can dilute some solutions, and oxidation or other chemical changes may alter etchant behavior over time. Regular solution replenishment or replacement schedules should be established based on processing volume. For critical applications, real-time monitoring of solution properties may be warranted to ensure consistency. Modern fabrication facilities often employ automated chemical management systems that continuously monitor and adjust solution parameters such as concentration, pH, and oxidation-reduction potential to maintain optimal etching conditions throughout extended production runs.

Proper agitation during wet etching ensures fresh reactants reach the silicon surface and reaction products are efficiently removed. Various agitation methods include magnetic stirring for gentle, continuous agitation, ultrasonic agitation for enhanced mass transport and improved uniformity, and megasonic systems for gentler agitation of delicate structures. Wafer rotation systems can ensure even exposure across large substrates. The choice of agitation method impacts not only etch rate and uniformity but can also affect surface roughness and feature profiles. Optimization for specific applications using 150mm silicon wafers or other products may require experimental evaluation of different approaches. Advanced agitation systems often incorporate programmable patterns and variable intensity to optimize mass transport while minimizing mechanical stress on delicate structures.

Safety Considerations in Silicon Wafer Etching

Silicon wafer etching processes often involve dangerous chemicals and equipment that require strict safety protocols. Ensuring a safe working environment is really important for anyone involved in these processes, from research laboratories to industrial manufacturing facilities. Proper safety measures protect people, equipment, and the environment from potential hazards associated with etching operations. The development and implementation of comprehensive safety programs should be considered an essential component of any silicon etching operation, not just a regulatory requirement.

The chemicals used in silicon etching present various hazards that require specific safety measures. Hydrofluoric acid (HF) is particularly dangerous, capable of causing severe tissue damage and systemic toxicity through skin contact. Strong bases like KOH and TMAH can cause chemical burns and eye damage. Oxidizers such as hydrogen peroxide and nitric acid present fire and explosion risks, and many etchants release toxic or corrosive vapors during use. Essential safety equipment includes chemical-resistant gloves appropriate for specific etchants, face shields and safety goggles, chemical-resistant aprons or full-body protection, proper ventilation systems and fume hoods, and emergency eyewash stations and safety showers. All personnel should be thoroughly trained in chemical handling procedures and emergency response protocols before working with etching chemicals.

Dry etching systems present their own set of safety considerations. High voltages and RF power sources create electrical hazards, while vacuum systems present implosion risks if damaged. Process gases may be toxic, corrosive, or flammable, and plasma emissions can include harmful UV radiation. Proper training on equipment operation, emergency shutdown procedures, and maintenance protocols is essential. Systems should include appropriate interlocks and safety features to prevent operator exposure to hazards. Modern dry etching equipment typically incorporates multiple safety systems, including automated gas detection with emergency shutdown capabilities, redundant power interlocks, and fail-safe designs that default to safe states in the event of system failures.

Proper disposal of etching waste is critical for environmental protection and regulatory compliance. Spent etchants require neutralization or specialized disposal, rinse waters may contain hazardous components requiring treatment, and solid waste such as used masks and wafer fragments may require special handling. Exhaust gases from dry etching systems may need scrubbing or abatement to prevent environmental contamination. Established waste handling procedures should be followed for all etching processes, with appropriate documentation maintained according to local regulations. Many facilities have implemented waste minimization programs that include chemical recycling, process optimization to reduce chemical consumption, and alternative chemistries with reduced environmental impact.

Conclusion: Selecting the Optimal Etching Technique

Choosing the best etching technique for a specific application requires careful consideration of various factors including feature size requirements, aspect ratios, material compatibility, and available equipment. The optimal approach often depends on balancing technical requirements with practical constraints such as cost, throughput, and environmental considerations. A systematic evaluation of these factors, combined with an understanding of the fundamental principles and limitations of different etching techniques, enables informed decision-making that optimizes both process performance and economic considerations.

When determining the optimal etching approach, consider these key factors: feature size and geometry (sub-micron features typically require dry etching techniques, while high aspect ratios may necessitate specialized processes like DRIE); material compatibility (selectivity requirements between silicon and other materials, mask compatibility with chosen etchants); equipment availability and cost (wet etching generally requires simpler, less expensive equipment, while advanced plasma systems represent significant capital investment); and environmental and safety considerations (chemical hazards, waste management requirements, facility ventilation and safety infrastructure). Professional silicon wafer suppliers can provide technical guidance to help customers select the most appropriate silicon wafers and processing approaches for their specific applications.

Many advanced applications benefit from combining multiple etching techniques in hybrid and multi-step approaches. These might include initial deep etching with DRIE followed by wet etching for surface smoothing, anisotropic wet etching for gross material removal with plasma etching for fine features, sequential etching steps with different chemistries for complex multilayer structures, or combinations of isotropic and anisotropic processes for specialized geometries. These hybrid approaches leverage the strengths of different techniques while mitigating their individual limitations. Developing optimized multi-step processes often yields superior results compared to single-technique approaches.