What is Thermal Oxide Deposition on Silicon?

This process creates thin layers of SiO2 on silicon surfaces. These layers act as gate oxides and dielectric materials in semiconductor devices. As these layers grow, they make it harder for oxygen to reach the silicon substrate. The oxygen reacts with the silicon to form SiO2.

Get Your Quote FAST! Or, Buy Online and Start Your Research today!

Thermal Oxide Silicon Wafers for Spectroscopic Research of Flourescent Nanoparticles

A research client asks us which wafers they should use for their nanoparticle research.

The following wafers were purchased.

Si Item #452

100mm P(100) 0-100 ohm-cm SSP 500um Test Grade

Si Item #2795

100mm P/B <100> 1-20 ohm-cm 625um SSP Test w/ 300nm Wet Thermal Oxide

We have oxide thicknesses 10nm - over 10 micron thick. Buy as few as one wafer if sold online.

Thermal Oxide to Fabricate Tomorrow’s Atom Thick Transistors

You don't need Moore's law to show you that transistors are getting smaller every year. Scientists and engineers are pushing this trend to almost absurd limits by making devices from layers of atomic thickness.

The most well-known material is graphene, a sheet-shaped carbon plate with a thickness of only a few nanometers. But graphene is not really a useful substance for the manufacture of transistors; it is a semiconductor built with all the properties that make it semiconductors, but without the electronic properties.

Researchers have investigated the use of transition dialcogenics made from metals that carry the chemical formula MX2. These generate individual atomic layers, which, unlike graphene, are natural semiconductors.

These materials have the potential to shrink transistors to atoms - thin components - before today's silicon technology takes its course. Although this idea is exciting, researchers believe that 2D materials will appear in the near future, even if silicon still prevails. Researchers are developing technologies that could integrate 2d semiconductors into silicon chips, improve their capabilities and simplify their design.

Devices Made With 2D Materials

A type of device used in digital things consists of a channel region that connects the source and outlet electrodes, a gate dielectric that covers the channel on one or more sides and contacts the gate electrode, and a dielectric on the other side. The so-called short channel effect in transistors is a consequence of the continuous shrinking of transistors over the decades. By applying a voltage to the gates relative to a source, the layer of mobile charge carriers is created, whereby channel areas form a conductive bridge between the sources and the outputs and allow the current to flow.

The resulting fin-shaped structure provides better electrostatic control, but when the channel becomes smaller, electricity seeps through even when there is no voltage at the gate, wasting electricity. The Finfet transistor structure, which is developed and used in today's most advanced processors, is an important short channel effect that counteracts the effect of channel regions being thinned out and surrounded with multiple sides.

Certain 2D semiconductors could circumvent the short-term channel effect by replacing silicon in the device's channel. By using only one semiconductor layer, 2d semiconductors could offer a much more efficient and cost-effective alternative to silicon, the researchers say.

With such limited power flow, there is little room for charged carriers to sneak in while the device is turned on. This means that transistors can shrink without having to worry about the consequences of the short-term channel effect.

But 2D materials are not only useful as semiconductors; some, such as hexagonal boron nitride, can act as gates or dielectrics, and had the ability to form a combination of them into a complete transistor. Add graphene instead of metal as part of a transistor, and you have the ability to form combinations of 2d materials into complete transistors. They may have the same properties as silicon dioxide, which was routinely used for this task until about a decade ago.

2D materials are likely to arrive in the form of low-power circuits that have the same properties as silicon, but much smaller footprint and lower power consumption. Indeed, individual research groups have been building such devices since 2014, and there is even talk of what a full-fledged 2D transistor could be, which is only a fraction of today's devices. Although these prototypes are much larger, one could imagine that they will be reduced to a size of only a few nanometers.

As traditional transistor scaling becomes more and more difficult, engineers are looking for ways to add functionality to the interface layer. Chip manufacturing is divided into two parts: the front part of the line consists of a process that often requires high temperatures, changes the silicon itself, and implants a doping agent to define the parts of each transistor. The rear end of this line is formed by connecting the transistors with many layers of connections to form an electric circuit and supply current.

Conventional silicon processes cannot be carried out at high temperatures because the heat would damage the underlying component compounds. Many systems are therefore based on materials that can be processed into devices at relatively low temperatures.

Getting 2D Semiconductors On A Silicon Wafer

CMOS circuits are the backbone of today's logic, because they do not consume electricity when they move from one state to another. One of the advantages of using 2D semiconductors instead of other candidates is that they are composed of two types of semiconductors, the p-type, which carries a positive charge, and the electron type, which carries a p-type, out of necessity. However, the physics underlying these materials suggests that we can get there by constructing dielectric metal - contacting semiconductors. In a recent paper in the journal Physical Review Letters, a research team at the University of California, Berkeley, identified the preferred 2d semiconductors in a silicon wafer as a possible solution.

The possibility of producing a p-type device would allow the use of repeaters that transmit data that must be transported relatively far from the chip. Normally the transistors involved are in silicon, and the repeater transfers data from one layer to the next. This means that the signal must climb a stack of connectors until it reaches a layer where it can travel part of the way to its destination, and then return to silicon to be repeated.

The Repeater's long-distance connection is more like a motorway service station: you don't have to drive from the motorway to the city center of a crowded city to buy petrol before you return.

By adding silicon, moving the repeater to a connecting layer saves space for more logic. This not only saves the time the signal takes, but also avoids the need to use a large number of chips with high - powerful, low - bandwidth. Repeaters are not the only potential application: they are also useful for other applications, such as smartphones and wearable devices.

One thing all these circuits have in common: they do not require a large amount of electricity, and one layer of 2D material would probably be enough. The 2D material could also be used to build back-end line circuits, as they occur in smartphones and wearable devices. It will be possible to require less from the back of the circuit, for example due to the use of a smaller number of repeaters on a silicon wafer.

The team from Imec is working to develop a process that is suitable for these applications. The first step is to identify the right materials for the 2D-FET architecture and the right silicon wafers. They therefore compare advanced silicon finFET devices with the latest state-of-the-art in the field of high-performance, low-performance and high-efficiency fat devices.

Although researchers have most experience with molybdenum disulfide (Mos2), the experimental equipment for its production is not yet at the most advanced stage.

Imec considered all the options, but decided that Mos2 was not the answer for them and looked for other options.

Researchers were able cultivated the material using a common process that allows crystals to be grown on the surface by chemical reactions. We were able to produce a high-quality version on a 300 mm silicon wafer, but we also concluded that the single-gate FET architecture works better in the semiconductor channel area than in the back end of the line, which is less required by our application. Instead, we conclude that stacked nanosheet devices have the best power performance in terms of power consumption, meaning that tungsten disulfide, the most efficient material for stacking nanosheet devices, can drive most of the electricity. One thing we did know before we came to this conclusion, however, was that it is very expensive.

Researchers chose this approach because of the cost of tungsten disulfide and the high performance of our device, as well as the high power consumption.

However, the benefits of MOCVD growth come at the expense of higher temperatures. High temperatures are prohibited because they could damage the underlying silicon components

The wafer has a layer of material that melts away with a laser during illumination and then comes into contact with a specially prepared wafer.

The silicon on the target wafer, which would have transistors with several layers of interconnection layers, is tipped over and the 2D material is peeled off the growth wafers. The adhesive layer also has a layer of ws2 on top, and this is pressed into the adhesive side of the wS2 - coated wafer. During the laser scan, it scans the layer, breaking off the largest or entire wafer and leaving only adhesives and w s2 for the target waves.

The adhesive is removed with a chemical plasma, and only the processed silicon to which wS2 is attached is left, held by Van der Waal's forces. The improvement consists in reducing defects caused by unwanted particles on the wafer surface and eliminating defects that occur at the edges. This process is complicated to embed and process, but it is a step in the right direction.

Once The 2D Semiconductor Has Been Deposited

Perhaps the most important issue to be resolved is the creation of shortcomings in WS2, and there have been some successes on this front, but major challenges remain. The components used for the deposition of the 2D semiconductor consist of two components: the silicon wafers and the semiconductors themselves.

In ordinary silicon components, charges can get caught up in imperfections and cause defects that severely impair the performance of the 2D device. In silicon wafers, electrons and holes can scatter as they try to move through the device and slow things down. But in 2D semiconductors, the scattering problem is more pronounced because the interface is located in a channel.

The structure of the two-gate works in a device that should actually exist at the interface layer of the chip and not on the surface of the chip itself. The semiconductor tungsten disulfide is barely visible between the metal source and the drain, and another dielectric separates it from the two gates. Sulphur vacancy is one of the most common deficiencies affecting equipment in this canal region. Researchers investigated how different plasma treatments could make the semiconductor tungsten disulphide in the channel more stable and less susceptible to defects. Oxygen attacks the sulfur cavities and the defect area increases, which prevents further defects from forming after the growth of the monolayer. WS2 and other 2D materials age and continue to decompose even if they are already defective.

They lack the dangling bonds that would otherwise help the dielectric to attach to the surface. Placing insulating materials on the 2D surface to create a gate between the diesels is a real challenge. Defective semiconductors are not the only problems researchers have in the manufacture of 2-D components. We have found that storage of samples in an inert environment makes a decisive difference in preventing the spread.

Researchers are currently investigating two ways that could help: one is to reduce the growth temperature, and the other is to release the surface. The reduced temperature increases the probability that gas molecules will adhere to the surfaces of WS2, even if no chemical bonds are present. Gas molecules are formed in a single layer and then a second gas is added, which reacts with the adsorbed first gas, leaving a gas molecule with a chemical bond between the gas and a dielectric in the form of an adhesive bond.

The other option is to improve ALD by using very thin oxidized layers such as silicon to promote growth of the ALD layer. In this method, the very thin silicon layer is deposited with thermal oxide and oxidized, while the regular AL-D deposition of thermal oxide takes place, with particularly good results achieved by evaporation.

The challenge in making a superior 2D device is to select the right metal that can be used as source and outlet contact. A metal can change the properties of the device depending on the working function. For example, the minimum energy required to extract electrons from a metal can create a contact that can easily inject electrons, or one into which holes can be injected, and vice versa.

Researchers studied a wide range of metals and came into contact with ws2 nanosheets. We found out that the highest inrush current in the N device with magnesium contact was reached. What will the metals of future P-devices look like and how will they work?

Evaluating the upper limit of a device's performance is a challenge, but this shows the path we need to take to get there. Researchers used a gated device similar to the one described in the benchmark.

In laboratory equipment, the researchers were able to measure that it is almost as crystalline as silicon, and this is the theoretically predicted maximum. We have built a small, naturally flaky flake (WS2) that has fewer defects than semiconductor wafers on the wafer scale. This is due to the excellent mobility of natural materials, which is not possible with materials synthesized on 300 mm wafers and which currently only reach a few square centimeters per volt per second.

One of the biggest challenges for the development of 2D semiconductors is to increase the mobility of charge carriers to a level comparable to silicon. For example, we know how to grow the material and transfer it to a 300mm target wafer, but we have no idea how to integrate the critical gate dielectric. The team has a good understanding of some of the major challenges facing the development of 2D semiconductors.

Solving these challenges will allow the development of powerful devices that reduce the atomic layers. This could initially bring new capabilities that require less demanding specifications, while silicon is being further reduced, but as we have already noted, this is still a significant problem. It will take a lot more work than the current state of the art in the field of art.

285nm Thermal Oxide for 2D Materials Research

An Assistant Professor requested the following quote:

It’s going to have to be a Si/SiO2 structure. Do you have any of those in stock with parameters similar to what I sent? It’s fine if the oxide is a little thicker.

These specs are being used by most researchers exploring 2D materials.

Wafer width: 3-4 inches

Oxide Thickness: 285 nm

Wafer thickness: 525 micron

Resistivity: 0.001-0.005 ohm-cm

Type/Dopant: P/Boron

Orientation: <100>

Front Surface: Polished

Back Surface: Etched

Reference #209352 for specs and pricing.

Is Thermally-Grown Oxide Sufficient for 2D materials Growth?

A physics PhD student requested the following answer:

Question:

I am interested in finding out about your SiO2-on-Si wafers. Is thermally-grown oxide sufficient for 2D materials growth? In my experience, it is quite rough and therefore not as good as CVD-grown oxide. Is there a margin of error in the 285 nm oxide thickness? I have seen some wafers on the market that have a +/- 5% variation in the stated thickness, which seems quite large to me. I look forward to your response.

Answer:

Thermally-grown silicon dioxide (SiO2) is a commonly used substrate for the growth of certain 2D materials, particularly graphene, due to its well-understood properties and the ease with which it can be prepared. However, whether it is sufficient or ideal for the growth of 2D materials depends on several factors:

-

Type of 2D Material: Different 2D materials have different substrate requirements. Graphene, for instance, can be grown on thermally-grown SiO2, but other 2D materials like transition metal dichalcogenides (TMDs) might require different substrate characteristics for optimal growth.

-

Quality Requirements: For high-quality, defect-free 2D materials, the substrate's properties are crucial. Thermally-grown SiO2 provides a smooth, amorphous surface which is beneficial for graphene growth. However, for other materials or for applications requiring extremely high-quality films, more specialized substrates might be needed.

-

Growth Method: The growth technique plays a significant role in determining the suitability of a substrate. For example, chemical vapor deposition (CVD) of graphene on SiO2/Si substrates is a common approach, but other methods may have different substrate requirements.

-

Electronic Properties: The electronic interaction between the 2D material and the substrate is important, especially in electronic applications. Thermally-grown SiO2 is electrically insulating, which can be advantageous for certain applications but might not be ideal for others where a conducting or semiconducting substrate is required.

-

Scalability and Cost: Thermally-grown SiO2 on silicon wafers is a cost-effective and scalable option, making it attractive for commercial applications.

-

Compatibility with Post-Processing: Some post-processing techniques might require specific substrate properties. The compatibility of thermally-grown oxide with these processes should be considered.

In summary, while thermally-grown oxide is frequently used and sufficient for the growth of some 2D materials like graphene, its suitability for other materials or specific applications depends on various factors including the material properties, growth method, desired quality, and application requirements. Research and development in this field are ongoing, and new substrate materials are continually being explored to optimize the growth and properties of different 2D materials.

Reference #228250 for specs and pricing.

Smooth Silicon Surface for 2D Material Topology Research

A chemical engineer requested help with the following:

I am looking for the substrates for the following requirement.

Very smooth surface. Nearly the same like the silicone wafer. We want to deposit 2D materials to evaluate the topography.

Flexible. We want to apply the strain on the substrates. More than 20%.

No temperature withstanding requirement.

Do you have any recommendation?

Reference #228944 for specs and pricing.

Oxidized Silicon Substrates for Depositing Thin Films

A researcher studying solid state physics and magnetism requested the following quote:

I am looking for square oxidized silicon substrates with size of 1 cm by 1 cm or 2 cm by 2cm and standard (100) orientation of the silicon. Before we purchased such substrates from a company that was cutting standard larger oxidized silicon wafers into square pieces. The exact size of the latter wafers is less relevant, but obviously larger wafers can be cut in square pieces in a more efficient way. Important is to avoid the presence of dust particles or other contamination on top of the oxidized surface as a result of the cutting process. The oxide thickness we need is 300 nm and we are looking for substrates with highly doped silicon (the exact dopant is not very relevant, we just need a high electrical conductivity) as well as to substrates with low doping (the silicon as a low electrical conductivity). Do you have such substrates available and what would be the price and the delivery time?

The pieces of oxidized low-doped silicon wafer will be used as substrates for depositing thin films and (aggregates of) nanoparticles which will be characterized by x-ray diffraction + reflectometry and by electrical transport measurements at low temperatures. The pieces of oxidized highly-doped silicon wafer will be used to deposit graphene or other 2D materials with a back gate attached to the back side of the highly-doped silicon, resulting in an FET configuration. Standard quality of the silicon should be OK since we will not define any devices in the silicon itself. On the other hand, the flatness of the oxidized silicon surface should be very good. At this point, it is difficult for me to give more quantitative information.

Concerning the number of pieces we want to order, this will of course depend on the price per piece. If possible we want to order at least 100 pieces of the low-doped silicon and at least 50 pieces of the highly-doped silicon.

Reference #233506 for specs and pricing.

What is the cause of discoloration of a Arsenic Doped Silicon Wafer after Thermal Oxide Deposition?

A PhD candidate researching 2D Materials requested help with the following question:

Question:

I am having difficulty identifying the side containing the thermal oxide layer on the the N-type arsenic doped silicon wafers we purchased. We would greatly appreciate your guidance. I am working on synthesizing 2D thin monolayered materials on these substrates.s. I am having difficulty identifying the side containing the thermal oxide layer and would greatly appreciate your guidance. I am working on synthesizing 2D thin monolayered materials on these substrates.

The issue I'm encountering is that both sides exhibit different colors. The 300 nm thermal oxide layer should have a blue to violet color. I expected both sides, if containing the 300nm thermal oxide, to display the same color. This discrepancy is making it challenging for me to identify the side housing the 300nm layer. I've included the images in the previous email for your reference.

Answer:

The blue-violet color observed in thermal oxide grown on an n-type arsenic-doped silicon substrate is primarily due to thin-film interference effects. This phenomenon occurs when light reflects off both the top surface of the oxide layer and the oxide-silicon interface, creating an interference pattern due to the differing path lengths of the reflected light waves.

Reference #279766 for specs and pricing.

Here are the key factors contributing to this effect:

-

Oxide Thickness: The thickness of the thermal oxide layer plays a crucial role in determining the color. The oxide layer acts as a thin film, and its optical thickness (physical thickness times the refractive index) determines which wavelengths of light will constructively or destructively interfere. Different thicknesses will reflect different wavelengths of light, leading to different colors. The blue-violet color suggests a specific range of thicknesses where the interference causes blue-violet light to be constructively interfered and therefore more prominently reflected.

-

Refractive Indices: The refractive indices of the silicon dioxide layer and the underlying silicon substrate also influence the interference pattern. Different materials have different refractive indices, affecting how light bends when entering and exiting the material and thus affecting the interference.

-

Angle of Incidence: The angle at which light strikes the oxide layer can also affect the perceived color, as it changes the path lengths of the reflected light rays.

-

Arsenic Doping: While the doping itself doesn’t directly cause the color change, the presence of arsenic can affect the silicon substrate's properties, including how it interacts with the oxide layer during the thermal growth process. However, the primary driver of the color is still the interference effects in the oxide layer, not the doping of the silicon.

It's important to note that while the arsenic doping influences the electrical properties of the substrate, the visual appearance (in terms of color) of the thermal oxide layer is largely governed by optical physics rather than the chemical properties of the dopant.

Thermal Oxide Deposition

We have access to the best equipment for both Wet and Dry Thermal Oxide Deposition on Silicon Wafers.

Below are just a small sample of the specs that you'll find online. We have both wet and dry and can deposit on one or both sides of the wafer. You can buy as few as one wafer!

We can also deposit oxide on the following tough to find spec:

100mm N/Ph (100) 0.001-0.005 ohm-cm 500um SSP or DSP Oxide Thickness is up to you!

| Dia |

Type |

Dopant |

Ori |

Res ohm-cm |

Thk |

Pol |

Oxide Thk |

| 50.8mm |

P |

Boron |

(100) |

1-10 |

280μm |

SSP |

285nm Wet Oxide |

| 100mm |

P |

Boron |

(100) |

1-10 |

500μm |

SSP |

300nm Wet Oxide |

| 100mm |

N |

Phos |

(100) |

1-10 |

500μm |

SSP |

300nm Wet Oxide |

| 100mm |

P |

Boron |

(100) |

1-10 |

500μm |

SSP |

100nm Wet Oxide |

| 100mm |

P |

Boron |

(100) |

1-10 |

500μm |

SSP |

10,000nm (10μm) Wet Oxide |

| 76.2mm |

P |

Boron |

(100) |

5-10 |

380μm |

SSP |

100nm Dry Oxide |

| 100mm |

P |

Boron |

(111) |

<0.005 |

500μm |

SSP |

50nm Dry Oxide |

| 150mm |

P |

Boron |

(100) |

0-100 |

650μm |

SSP |

300nm Wet Oxide |

| 200nm |

P |

Boron |

(100) |

>1 |

750μm |

DSP |

100nm Wet Oxide |

| 300nm |

P |

Boron |

(100) |

1-10 |

850μm |

DSP |

300nm Wet Oxide |

SiO2 thin film layers are used as dielectric material

Silicon dioxide is an amorphous material used in capacitors and electronic devices. It also serves as a dielectric insulator and a structural layer in micromachining processes. Silicon dioxide thin films are grown on silicon wafers. High quality oxide films offer excellent electrical insulation with resistivity values in the range of 1010 ohm/mK. Thermal conductivity is relatively low at 1.4 W/mK. The properties of the films vary with the amount of silicon and the type of process used.

The increasing demands for microelectronic devices have led to increased demand for high-k materials. Low-k materials reduce RC delays in interconnects, while high-k materials improve the performance of nonvolatile memory devices. High-k materials also allow for continued scaling of gate insulators and ultra-thin film stacks in nanometer-scale devices. This research may pave the way for higher-quality silicon-based devices.

A dielectric material that increases the electrical conductivity of a device is the inter-level dielectric (ILD). Most inter-level devices use silicon dioxide as a dielectric because it has a low dielectric constant. However, the dielectric constant is higher than the minimum required for inter-level devices. To reduce the dielectric constant, materials for ILD applications have been developed. The key design principals include reducing moisture absorption, polarization strength, and density.

Typically, silicon dioxide thin film layers are used as a dielectric material in MEMS devices. The process of creating a silicon oxide layer on silicon wafers involves oxidizing silicon with oxygen. This process can be performed using high-dry or wet oxidation, with the latter being the preferred method for thicker films. However, the growth rate is slower and results in a weaker material. Therefore, LTO is not suitable for applications requiring high electrical integrity.

Silicon nitride thin film layers are also used as a stop in chemical mechanical polishing processes. PECVD and LPCVD are two processes used for silicon nitride deposition. Further, the silicon nitride process is used for producing SiO2 thin film layers. These materials are also commonly used in semiconductors and optical devices. If you're wondering if SiO2 is the right material for your applications, read on.

TEOS-based silicon dioxide process has mostly replaced the LPCVD-based process for silicon dioxide deposition. These processes produce silicon dioxide films with properties close to thermal oxide and have good conformality. But there's a downside: LTO films have poor conformality. If the oxide is too thick, electrons can tunnel through it, producing gate leakage currents of up to 100 A/cm2 at 1V, which would completely destroy the transistor's functionality.

High-k dielectrics such as HfSiON are not as good as silicon dioxide. The former is susceptible to crystallization during dopant activation annealing. However, the latter does have the advantage of being stable, making it a better dielectric material for semiconductor devices. Furthermore, high-k materials enable the further miniaturization of microelectronic components, extending Moore's law.

They are Integrated in MEMS

The process of thermal oxide deposition on silicon is a common fabrication method for MEMS devices. The process improves the surface of silicon wafers, removing unwanted particles and resulting in thin films with high electrical strength and purity. Thermal oxide deposition is more uniform than ion sputtering and offers several benefits. Here are the pros and cons of thermal oxide deposition on silicon.

MEMS and NEMS are a significant technological advance within the last 20 years, and recent advancements have been facilitated by advances in materials and processes. While initial MEMS developments capitalized on a mature infrastructure for Si-based devices, recent advances have incorporated materials that have little to do with IC fabrication. This trend is likely to continue as more applications for these devices are identified. In the meantime, there are several promising developments underway.

The process also allows for adjustable layer tension. By adding a thermal oxide layer to the surface of silicon, the process minimizes the impact of the undercut region. Moreover, the thermal oxide layer acts as a releasing barrier, preventing etching of the inactive region. LPCVD polysilicon is then deposited to fill the cavities. Then, it is flattened using a CMP process. The bottom Mo electrode is manufactured with a gentle angle, which is beneficial for the growth of AlN piezoelectric layer. This prevents the device from breaking due to overheating.

Anodic oxidation on silicon is a very efficient process for developing uniform silicon dioxide thin films. The rate of growth of the oxide film is primarily influenced by the voltage applied and linearly proportional to it. In addition to this, mechanical agitation of the electrolyte solution is beneficial for the chemical structure and growth rate of the oxide films. The current density also affects the growth rate of the oxide film.

There are several advantages of thermal oxide deposition on silicon. First of all, it is more effective than other processes for oxidizing silicon. For example, it is much easier to process silicon in this way, resulting in higher quality and higher reliability. Additionally, the process is faster than other techniques, making it the preferred method for MEMS manufacturing. These benefits make thermal oxide deposition on silicon the best choice.

The oxide film grows in three steps. First, the oxygen is transported to the surface and second, it is diffused through the oxide. Then, the oxygen reacts with silicon at the interface. The process is slower when the oxide layer is thicker, but the growth time depends on its thickness. In RTP systems, thin oxides can be grown at reduced pressures. Third, thermal oxide is a dense material that resists etching.

Thermal Oxide Used as Gate Oxides in Semiconductor Devices

A thermal oxide is a thin film that is a building block for semiconductor devices. It is a good dielectric thin film and is typically found on semiconductor devices as a gate oxide or field oxide. Gate oxides are very thin films that cover the active region of transistors. Thermal oxides are produced using two different methods, wet and dry. Read on to learn about the two different processes and what each type of thermal oxide is used for.

Wet thermal oxide is a type of thermal insulator that has low leakage current. This makes it useful for photolithography masking. It is deposited at high temperatures without using solvents. Silicon containing films are used as gate insulators in display devices. To produce a high-quality gate insulator, a conductive film must resist heat. Wet thermal oxide is an excellent choice.

The most commonly used thermal oxide is a wet one. It's not designed for insulating properties, but it's useful for photolithography masking. However, it's too porous to be a good insulator. Dry thermal oxide, on the other hand, is better because it undergoes annealing while forming gas. In addition to wet thermal oxide, Dry Thermal Chlorinated Oxide is used as a gate oxide in semiconductor devices.

Early life dielectric breakdown is a major concern for the semiconductor industry. As features of the device get smaller, the thickness of the oxide must also decrease. As a result, thin layers become more susceptible to voltages. Some of the thinnest oxide layers are less than 50 angstroms thick. Even the thinnest oxide layers are vulnerable to breaking down when voltages reach eight to eleven MV per cm of thickness. The breakdown process can be categorized as time-dependent or EOS/ESD-induced.

Gate oxides are dielectric materials that separate the conductive channel from the gate terminal. Gate oxides are produced through thermal oxidation of silicon. This is followed by self-limiting oxidation and then a conductive gate material is deposited over the gate oxide layer. This is the key to the functional properties of the gate. However, the quality of the gate oxides will ultimately affect the final performance of the device.

Silicon carbide is a compound semiconductor that can be grown on a SiC substrate. This compound semiconductor has excellent semiconductor properties and is expected to be used in power semiconductor devices in the future. Its crystalline polymorphism makes it possible to crystallize into various forms. Single crystals of SiC are now being produced and have a wurtzite structure. In addition, SiC has a wide band gap and can be applied in a variety of semiconductor applications.

Video: What is Dry Thermal Oxide

What is Gate Oxide?

If you're wondering what is Gate Oxide, this article can help you. Here's a quick overview of the material's properties. Its thermal conductivity is very similar to that of silicon, and its electrical resistance is much higher than that of copper. Because of this, gate oxide is often referred to as "nano-scale silicon".

The intrinsic breakdown field of SiO2 is still over 10 MV/cm. But due to the larger bandgap, tunneling currents in the gate oxide are much larger. The gate leakage current is much higher in SiC/SiO 2 systems. A gate oxide layer is important in semiconductors because it isolates the drain and source. However, it is important to understand that this material can break down under high voltages and can eventually be destroyed by a hotter external environment.

The material is also very thin, with a dielectric constant of 1.2 nanometers (nm) and an energy band structure similar to that of silicon. Its interface is rough and does not have the same smoothness as silicon. Despite its high-frequency characteristics, it is also important to note that a gate oxide's thickness can greatly affect its ability to conduct electricity. This material is essential to the design of transistors and other semiconductor devices.

The gate oxide is a thin layer of oxide that separates the gate terminal from the underlying conductive channel. Gate oxide is formed by thermal oxidation of silicon by a process called self-limiting oxidation. The conductive gate material is then deposited over the gate oxide. The resulting material is the semiconductor that controls the flow of current. This material is also called field oxide. The field oxide has a low electric resistance and is used to protect the transistors.

Thermal Oxide Deposition Silicon Explained

Silicon dioxide or silicon dioxide is one of the most common substances in semiconductor manufacturing. Silicon dioxide is often used as a mask layer for integrated circuits (IC) and as an oxide layer in semiconductors. Selective etching of oxide films is required to use silicon dioxide in integrated circuits, IC and MEMS manufacturing, and in the manufacture of electronic components. [Sources: 1, 2, 3]

The advantage of this technique is that the silicon oxide is deposited at a temperature of T2, which is compatible with a wide range of applications. The thermal oxide films are produced by a combination of the precursors described above and by the addition of a layer of silicon dioxide. In order to form a thick thermal oxide film with a thickness of 2500 nm or more, it is possible to prevent the occurrence of slipping and contortion and to carry out a satisfactory formation of thermal oxide films. Even if the temperature (T1) is higher than the temperature, slips and contortions are difficult and cracks can be prevented by forming a thin layer as it was formed in the previous stages. [Sources: 4, 5]

Thermal oxide films can be formed on silicon single crystal wafers, but only if the temperature of the heat treatment furnace is lower than 1200 Adeg (c), where the thermal oxide film forms at T1, it is not possible to sufficiently suppress the occurrence of slips and contortions during the formation of thermal oxide films. If the temperature of the heat treatments in the furnace is lower than 1200ADeg (c) the thermal oxide film forms in a thin layer. [Sources: 4]

On the other hand, wet oxidation of a steam mole diffusing into the oxidant will result in only one mole of silicon dioxide. The atmosphere oxidizes faster during the formation of thermal oxide films than in the atmosphere in which the oxide films are formed. If the thermal oxidation film has a temperature of 1200 A degrees (c) or more at T2 (or D2 in the preceding stage) and the oxidation rate is high due to the higher temperature, it is possible to efficiently and additionally form a thicker thermal oxide film, but only if the temperature at T2 is set at a temperature of 1200 Adeg (C) and more, making it more likely that the thick thermal oxide film will form in this subsequent stage. [Sources: 0, 4]

According to the present invention, the degradation problem is solved by depositing the silicon dioxide layer on a silicon nitride film. As described above, at a temperature of 1200 Adeg (C), thermal oxide films can be formed which allow the wafer to prevent adhesion to the boat by forming a thick thermal oxide film, and additionally, they can be formed continuously during the heat treatment of a furnace. In addition, in the next stage, at the temperature of T2 (or D2) and more than 1200 A degrees (c) or more, a thermal oxidation film may form, making them more likely to form a thicker thermal oxidation film than the previous stage as described below. [Sources: 2, 4]

In addition, a 5000 nm thick thermal oxide film forms which oxidizes at a temperature of 1200 Adeg (C) or more than 1200 A degrees (c). In addition, the thermal oxidation film is formed, which is 5000nm thick and can adjust to oxidation times of at least 1000 A degrees (c) and more. [Sources: 4]

By observing the dislocation of the slides by X-ray topography, a thermal oxide film is created with a thickness of 2500 nm. A thermal oxide film with a thickness of 6000 Nm form by observing slip contortions, observed by X-ray topology, and form at a temperature of 1200 Adeg (C) or more than 1200 A degrees (c) and more. Thermo-oxide films with the thickest thickness 3000 Nm and 5000 Nm are formed by observations of sliding contortions, observe the topographic method X - Ray and form at an oxidation time of at least 1000 A degrees (c). Thermal oxide foils with a thickness of 2500 Nm and a thermal oxidation film, which is thickened to 5000 Nm-shape A thermal oxide film has been formed by observing slides using X-ray methods. [Sources: 4]

The thermal oxidation films formed in Examples 1 and 2 are shown in Table 1, while the thermal oxidation films with a thickness of 2500 Nm and a thermal oxidation time of at least 1000 A degrees (c) and more are shown in Table 2. The thermal oxide films which are formed in Examples 2 and 3 and in Examples 4 and 5 are shown in Table 4. A thermal oxide film formed as a thermal oxidation film with an oxidation temperature of 1200 Adeg (C) or more is shown and in contrast Examples 5 and 6, with the same oxidation time and temperature as shown in Table 4, are disillusioned in Table 5. Comparable Examples 3 and 4 of the thermal oxide layer created by a thermal oxide layer with a thermal oxygen time of 1000 - 1200 A degrees (c) are shown in Table 3. [Sources: 4]

Sources:

[0]: https://nptel.ac.in/content/storage2/courses/103106075/Courses/Lecture29.html

[1]: https://www.hindawi.com/journals/tswj/2014/106029/

[2]: https://patents.google.com/patent/US4254161A/en

[3]: http://www.enigmatic-consulting.com/semiconductor_processing/CVD_Fundamentals/films/SiO2_properties.html

[4]: https://www.google.com/patents/US20130178071

[5]: https://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0103-97332001000200023

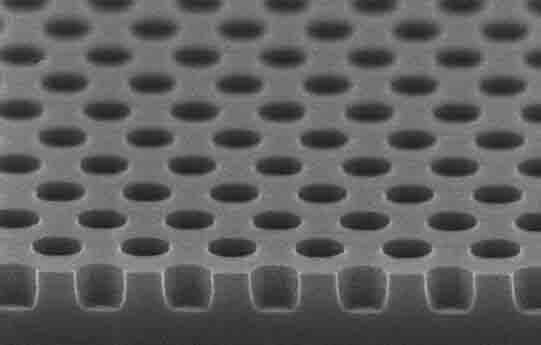

Thermal Oxide Silicon Wafers with Wells

A researcher asked us to quote the following: I am looking for Si wafers with wells with 1 or 2 microns in diameter and 500-1000 nm deep. Do you have these or can you make them?

UniversityWafer, INc. Quoted:

4" Si wafers with wells with 1.2 microns in diameter and 500-1000 nm deep. the wells pitch 3.0um,Any thermal oxide 4 inch Si wafer will do. Qty. 25 of them. Please reference #260328

Silicon Wafer with Well Holes Drilled